September 7, 2010

Goal: Giving feeling to a damaged hand or prosthetic limb

No longer science fiction, sense of touch within researcher's grasp

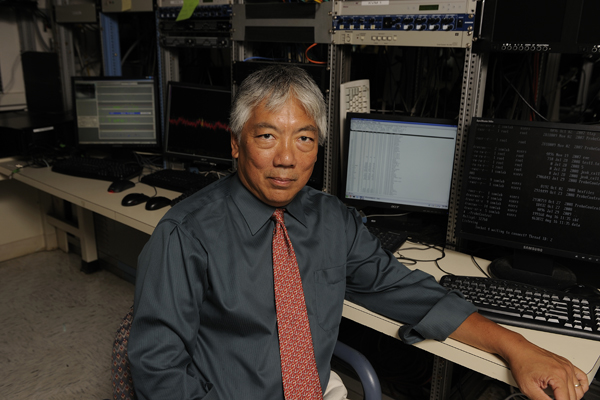

Neuroscientist Steven Hsiao of the Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute is leading a team working to decode how the brain processes sensations in hands. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

This is part of an occasional series on Johns Hopkins research funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. If you have a study you would like to be considered for inclusion, contact Lisa De Nike at lde@jhu.edu.

Back in 1980 when The Empire Strikes Back hit the big screen, it seemed like the most fantastic of science fiction scenarios: Luke Skywalker getting a fully functional bionic arm to replace the one he had lost to arch enemy Darth Vader.

Thirty years later, such a device is more the stuff of fact and less of fiction, as increasingly sophisticated artificial limbs are being developed that allow users a startlingly lifelike range of motion and fine motor control.

Johns Hopkins neuroscientist Steven Hsiao, however, isn’t satisfied that a prosthetic limb simply allows its user to move. He wants to provide the user the ability to feel what the artificial limb is touching, such as the texture and shape of a quarter, or the comforting perception of holding hands. Accomplishing these goals requires understanding how the brain processes the multitude of sensations that come in daily through our fingers and hands.

Using a $600,000 grant administered through the federal stimulus act, Hsiao is leading a team that is working to decode those sensations, which could lead to the development of truly “bionic” hands and arms that use sensitive electronics to activate neurons in the touch centers of the cerebral cortex.

“The truth is, it is still a huge mystery how we humans use our hands to move about in the world and interact with our environment,” said Hsiao, of the Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute. “How we reach into our pockets and grab our car keys or some change without looking requires that the brain analyze the inputs from our hands and extract information about the size, shape and texture of objects. How the brain accomplishes this amazing feat is what we want to find out and understand.”

Hsiao hypothesizes that our brains do this by transforming the inputs from receptors in our fingers and hands into “neural code” that the brain then matches against a stored central “databank” of memories of those objects. When a match occurs, the brain is able to perceive and recognize what the hand is feeling, experiencing and doing.

In recent studies, Hsiao’s team found that neurons in the area of the brain that respond to touch are able to “code for” (understand) orientation of bars pressed against the skin, the speed and direction of motion and curved edges of objects. In its stimulus-funded study, Hsiao’s team will investigate the detailed neural codes for more complex shapes, and will delve into how the perception of motion in the visual system is integrated with the perception of tactile motion.

The team will do this by first investigating how complex shapes are processed in the somatosensory cortex (the part of the brain that responds to touch) and second, by studying the responses of individual neurons in an area that has traditionally been associated with visual motion but appears to also have neurons that respond to tactile motion (motion of things moving across your skin).

“The practical goal of all of this is to find ways to restore normal sensory function to patients whose hands have been damaged, or to amputees with prosthetic or robotic arms and hands,” Hsiao said. “It would be fantastic if we could use electric stimulation to activate the same brain pathways and neural codes that are normally used in the brain. I believe that these neural coding studies will provide a basic understanding of how signals should be fed back into the brain to produce the rich percepts that we normally receive from our hands.”

Hsiao’s team’s investigations are among the 451 stimulus-funded research grants and supplements totaling more than $214.3 million that Johns Hopkins has garnered since Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (informally known by the acronym ARRA), bestowing the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation with $12.4 billion in extra money to underwrite research grants by September 2010. The stimulus package—which provided $550 billion in new spending, including the above grant—is part of the federal government’s attempt to bring back a stumbling economy by distributing dollars for transportation projects, infrastructure building, the development of new energy sources and job creation, and financing research that will benefit humankind.

Johns Hopkins scientists have submitted about 1,500 proposals for stimulus-funded investigations, ranging from strategies to help recovering addicts stay sober and the role that certain proteins play in the development of muscular dystrophy to mouse studies seeking to understand how men and women differ in their response to the influenza virus.

As of Aug. 31, 167 staff jobs have been created at Johns Hopkins directly from ARRA funding, not counting jobs saved when other grants ran out and not counting faculty and grad student positions supported by the ARRA grants.

Related websites

Steven Hsiao:

krieger.jhu.edu/mbi/research/hsiao

Steven Hsiao’s lab:

krieger.jhu.edu/mbi/hsiaolab