July 18, 2011

A century of medical illustration

In 1911, Johns Hopkins' Max Brodel founded the first program of its kind

Department chair Gary Lees, seated left, and other faculty and staff of Art as Applied to Medicine raise commemorative beer steins to founder Max Brodel, in painting. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

Max Brodel was a child prodigy of several sorts. Born in 1870 in Leipzig, Germany, Brodel took to the piano just after he learned to walk. At age 12, he could play Beethoven both beautifully and effortlessly, suggesting a future in music.

His true gifts, however, shone on paper and canvas.

During the summers of his late teens, Brodel would sketch museum-quality landscapes and figures to make some extra cash. Luckily for Johns Hopkins and the field of medicine, Brodel’s art didn’t sell well.

Needing money, Brodel applied his artistic talents to drawing kidneys and other body parts for the Anatomical Institute in Leipzig. He would later meet Carl Ludwig, the famous physician, who lured the then 18-year-old illustrator to the Institute of Physiology at the University of Leipzig.

With Leipzig an epicenter of medicine, Brodel met many visiting scholars, such as anatomist Franklin Mall, who urged Brodel to bring his talents to the new Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

The rest is illustrated history.

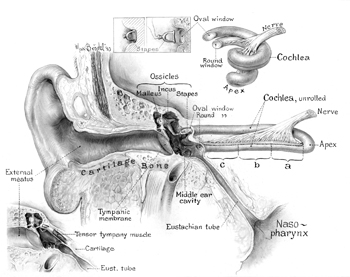

Max Brodel’s reconstruction drawing of the inner ear from serial sections of the temporal bone. The illustration appears in ‘Three Unpublished Drawings,’ 1946. Courtesy: The Brodel Archives

Brodel, who arrived in Baltimore in the winter of 1894, spent nearly 17 years illustrating for Johns Hopkins physicians, defining a professional field along the way, before founding the school’s Art as Applied to Medicine Department that sought to train medical illustrators to help physicians see how the human body works. The program was the first of its kind.

On July 20, the School of Medicine will celebrate the work of the German artist and the department’s first 100 years at an event to be held in the school’s Turner Auditorium and Turner Concourse. The all-day conference will include an unrivaled exhibition of medical art, an international array of speakers from the profession and an evening event featuring beer from Brodel’s own recipe and music written for his friend H.L Mencken’s Saturday Night Club.

Gary Lees, chair of Art as Applied to Medicine and only the fourth person to hold that position, says that the event will celebrate the past, present and future of the department—and the man who made it all happen.

“Brodel was a genius, and I don’t use that term lightly,” Lees says. “He was just so talented and gifted. He loved his art.”

When Brodel was 15, he had enrolled in the Leipzig Academy of Fine Arts, where he focused on precision and mastery. Upon graduation from the academy, Brodel worked on gross anatomical and histological drawings for Ludwig, a brilliant physiologist who notably advanced understanding of the kidney and renal function.

It was during his time in Ludwig’s laboratory that Brodel developed his doctrine of intimate observation. Brodel would routinely attend surgeries and autopsies, peering over the shoulder of the physician, listening to his descriptions and taking copious notes.

“The quote from Brodel that I love the most is to ‘leave paper and pencil alone until the mind has grasped the meaning of the object,’ ” Lees says. “Medical illustration is not drawing a pretty picture. It’s not just knowing the science. It’s being able to take science and the art and combine them to communicate. Today, we’re still doing that.”

Upon his arrival in Baltimore, Brodel was quickly employed by Howard Kelly, chief of Gynecology, as his illustrator for a two-volume textbook called Operative Gynecology. Brodel went on to work on other books authored or co-authored by Kelly, including those on diseases of the kidneys, ureters and bladder. He also illustrated Kelly’s journal articles and monographs. When time permitted, Brodel did illustrations for other Johns Hopkins physicians and surgeons, expanding his knowledge of anatomy, pathology and physiology.

Lees says that Brodel was in heavy demand.

“What Brodel had done was make Johns Hopkins physicians famous because their articles were illustrated beautifully with very accurate, educational art—which was unheard of at that time,” he says.

In 1911, when Kelly retired as chief of Gynecology, Brodel was left without consistent illustration work. To retain the outstanding illustrator, who was attracting strong interest from the Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins’ Thomas Cullen conceived of a department where Brodel could train students in the necessary knowledge and skills to become medical illustrators. Henry Walters, a Baltimore financier, philanthropist and art collector, agreed to support the venture. His endowment created the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, which opened in 1911.

In an article published in the September 1911 edition of The Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin, Brodel laid out his case for the creation of the department. “Its purpose,” he wrote, “is to bridge over the gap existing between art and medicine, and to train a new generation of artists to illustrate medical journals and books in the future and to spare them the years of trial and disappointment of their self-taught predecessors.”

The department’s courses were divided into two tracks, one for medical students and one for artists and art students. Brodel served as director until 1940. He died a year later, and at his funeral many famous Johns Hopkins physicians served as pallbearers.

“He was loved as a colleague and revered for his knowledge and his art,” Lees says.

He also left behind a vast legacy.

The department’s graduates went on to become medical illustrators in universities, hospitals, research institutes and clinics. Brodel’s own students would later make up a large percentage of the founding members of the Association of Medical Illustrators, which began in 1945. Between 1941 and 1952, Brodel-trained illustrators would go on to found and direct eight of nine similar medical illustration programs in the United States and Canada.

The need for increased communication in health sciences later prompted additional training in photography, medical models and exhibit production at the department. In 1959, the department began its degree of Master of Arts in Medical and Biological Illustration. Entrance requirements were increased, and a two-year curriculum was established.

Today, the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine is a leader in the field of visual communication for science and health care.

The department continues to teach traditional pencil to paper medical illustration while embracing the latest in communication technologies, such as the use of 3-D modeling, animation and the Internet. The program currently houses 12 full-time students, each with access to a state-of-the-art computer lab with multiple workstations, platforms, peripherals and resources.

As medicine, art media and communication technology evolve, Lees says, so does medical illustration.

“When the Web came in, it was an opportunity for medical illustrators to do much more in patient education. [People] are now on their computers looking up information on their own health care,” he says. “We use any medium and technique that can be used. The skill of the illustrator, however, remains to intimately know the anatomy and be able to tell that story.”

The department’s students attend both illustration and medical courses.

In the Surgical Illustration course, students must effectively illustrate four different procedures, such as neuro-, plastic, abdominal and cardiac surgery. To know their subjects, the students are enrolled in the Human Anatomy course with the medical students, and often stay on longer in the dissection room and view more autopsies than their medical student counterparts.

“Just like Brodel taught, they stare over the shoulder of the surgeon,” Lees says. “Why? This field is more than just seeing and hearing what is going on. Surgeons are wonderful teachers. They are constantly verbal. They tell residents such things as, ‘When you get your hand underneath the structure, watch out for these blood vessels.’ You can’t take a picture of that. A photo also can’t show what to focus on. You need an illustration for that.”

The department’s faculty produces illustrations, animations and graphic design for the medical, research and publishing communities. An anaplastology clinic within the department also creates facial and somatic prosthetics for patients and is in the process of establishing a one-year training program in clinical anaplastology.

Recent graduates of the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine have gone on to work at hospitals, clinics and universities, and in the world of television, including the National Geographic and Discovery channels.

Lees says that the students leave the program knowing how to illustrate for both medical professionals and a lay audience.

“It doesn’t matter what the medium is,” he says. “The message is all-important. I like to say that medical illustrators are either artistic scientists or scientific artists. Every one of us falls somewhere along the line. Sometimes we need to give up a level of artistic imagination to get the message across.”

For more on the July 20 event and the department, go to www.hopkinsmedicine.org/medart.