May 7, 2012

Interpreting history and landscape

‘Sculpture at Evergreen’ features installations by College Park students

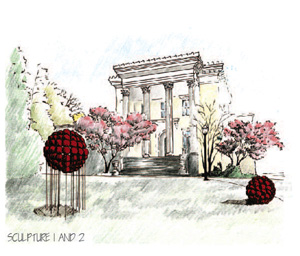

A preliminary sketch of ‘Entropy’ shows two of a series of red orbs that lead visitors from the front of Evergreen to a disused Olmsted Brothers–designed staircase descending into the woods. The concept was conceived by Melissa Lodge. Courtesy: Jack Sullivan

In the 19th century and early in the next, the lush grounds of Evergreen House featured seven elaborate glass conservatories with names such as Mushroom House, Melon House and Orchid House. The mistress of the mansion, Alice Whitridge Garrett, likely would have strolled into one of these houses on a spring day to care for ferns and exotic plants imported from England and Japan.

The houses were removed in the mid-1920s after Ambassador John Work Garrett and his wife, Alice Warder Garrett, established residency. The structures, they concluded, would be too costly to maintain. Today, only traces of the houses remain, such as the back brick wall of Mushroom House.

In the next five months, however, the spirit of these conservatories will be reborn with Ghost Greenhouse, one of 10 new site-specific, temporary outdoor installations that are both inspired by and created specifically for Evergreen Museum & Library and its 26-acre grounds.

Sculpture at Evergreen 7: Landscape as Laboratory will open with a public reception from 1 to 4 p.m. on Sunday, May 13, and will run until Sept. 30. It is guest curated by Jack Sullivan, a landscape architect and associate professor at the University of Maryland, College Park.

College Park students Melissa Lodge, Erin Battas and Christiane Machada work with the red orbs that will be part of ‘Entropy,’ shown in the sketch above. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

The exhibition features work developed by students in Sullivan’s fall 2011 course Design Fundamentals Studio, and refined and executed this spring by a smaller team of College Park graduate and undergraduate students through an independent study course with Sullivan.

For Ghost Greenhouse, the student artists erected a steel frame with the outline of a pitched roof, all painted white. In the sculpture’s center, colorful seasonal flowers will be planted to highlight the structure’s former purpose.

Sullivan says that Ghost Greenhouse and the nine other installations will beckon visitors to wander Evergreen’s grounds to learn more about the property’s landscape, architecture, history and collections.

Sullivan and the students received funds for fabrication, installation and de-installation. They were given the freedom to design whatever they wished, using whatever material they wanted. The only stipulation was that they come to Evergreen first and be inspired by the landscape or history of the 155-year-old estate.

Sullivan says that the student designers be- came “landscape sculptors,” drawing from the many resources at Evergreen and transforming the site through new objects and spaces.

“You could argue that in using student artists you are missing the depth a seasoned, professional artist might bring, but in exchange for that you have enthusiastic artists with less of a personal agenda who did their best to honor the landscape and the Garretts’ legacy,” Sullivan says.

For example, one student drew inspiration from Alice Warder Garrett’s art deco mirrored private bath when creating Illusion Garden, a twisting eight-foot-high, 45-foot-long chain-link fence arch with a center area featuring 20 mirrors that face each other. This particular installation will evolve over time, as a variety of tropical and native flowering vines will eventually cover the structure.

Other installations include a stream made of blue glass chips, canvas cubes, red orbs that lead down to a disused Olmsted Brothers–designed staircase into the woods, wind chimes hidden in a grove of trees and large metal disks suspended on poles made to represent umbrellas.

Evergreen House, an Italianate building with classical revival additions, was built in 1857 by the Broadbent family. It was purchased in 1878 by John W. Garrett, president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, for his son, T. Harrison Garrett. T. Harrison and his wife, Alice Whitridge Garrett, oversaw an ambitious program of renovation and construction on the estate during the 1880s. The couple’s eldest son, John Work Garrett, inherited the house in 1920, and he and his wife, Alice Warder Garrett, continued the tradition of expanding the house and adding to its collections. John Work Garrett died in 1942, bequeathing the estate to The Johns Hopkins University.

Alice Warder Garrett, who lived at Evergreen until her death in 1952, welcomed artists, performers and scholars there to draw inspiration from the property’s rich collections and impressive setting.

James Archer Abbott, director and curator of Evergreen, says that the Sculpture at Evergreen exhibition continues this legacy, allowing the museum’s historic collections to become a vibrant, creative source for new works and artistic innovations. Abbott says that Alice Garrett particularly wanted students involved in Evergreen’s use.

“She wanted the property to serve as a sort of open book, not just for professional artists but for students so they could come here and explore and create. She understood the temperament of artists and wanted to nurture them,” he says. “And with this experience with Jack Sullivan and his students at the University of Maryland, maybe we can get more students invested in this property.”

Hours of the exhibition, which is free and open to the public, are 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesday through Friday and noon to 4:30 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday (gates locked promptly at 5 p.m.) Walking maps and a free illustrated visitor’s guide are available in the Evergreen Museum & Library shop.

For more information on this and other Evergreen events, go to museums.jhu.edu/evergreen

.php.