January 30, 2012

Please do touch the art

Show at The Walters pairs research interests of professor and curator

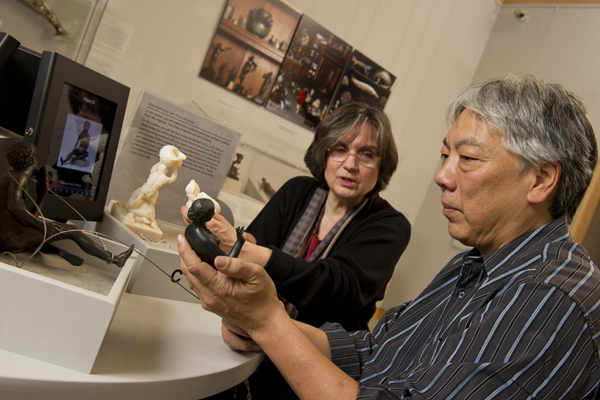

Johns Hopkins neuroscientist Steven Hsiao and Walters curator Joaneath Spicer are partnering to determine why physical contact with works of art can be so satisfying. Museum visitors can register their preferences and other reactions. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

It’s the first rule at any art museum: Do not touch the artifacts. Except at this museum and at this one time.

At the Touch and the Enjoyment of Sculpture: Exploring the Appeal of Renaissance Statuettes exhibition at The Walters Art Museum, open now through April 15, visitors are invited to disregard that decree and to hold, stroke and even caress the pieces.

In fact, handling the objets d’art, which include replicas of famous 16th-century statuettes that are part of the Walters collection, is one of the reasons behind the exhibition, explains neuroscientist Steven Hsiao of the Johns Hopkins Brain Science Institute, which is partnering with the Walters on this show, the fourth in a series of projects between the museum and Johns Hopkins.

“We’re challenging people to think about why physical contact with works of art can be so satisfying,” says Hsiao, whose research through the university’s Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute includes exploring many aspects of humans’ sense of touch. “In fact, as people browse the exhibition, we will be asking them to react to what they are seeing and feeling.”

But more on that in a moment.

Visitors touch and rate 22 replicas of works in the Walters collection. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

The installation incorporates 12 works of art from the Walters collection, along with 22 replicas for visitors to touch and rate. It melds the research interests of Hsiao, who specializes in many facets of touch in his work in the Department of Neuroscience in the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and that of Joaneath Spicer, curator of Renaissance and baroque art at The Walters, who studies the new taste in the Renaissance for collecting and commissioning small statuettes and other luxury goods that were satisfying to touch and handle.

But the special appeal of this exhibition lies in the opportunity to join in comparative experiments with the statuettes (well, replicas of them, actually).

“We’ll be asking visitors to handle them and to tell us what sculptures they prefer, and to rate how they like sculptures that have been modified in their shape and texture. This exhibition allows us to dissect why some objects feel better than others,” Hsiao says.

Visitors will register these preferences, and other reactions, on Apple iPads, and will be able to see a dynamic display of their responses. This data will be used as part of both Hsiao’s and Spicer’s research on tactile aesthetics.

Related websites

Johns Hopkins Brain Science Institute

Exhibition at The Walters Art Museum