August 31, 2009

LEGOs show researchers what happens inside lab-on-a-chip

“Dimensional analysis” studies a process at a different size and time scale while keeping the governing principles the same.

Johns Hopkins engineers are using a popular children’s toy to help them visualize the behavior of particles, cells and molecules in environments too small to see with the naked eye. These researchers are arranging little LEGO pieces shaped like pegs to re-create microscopic activity taking place inside lab-on-a-chip devices at a scale they can more easily observe.

These lab-on-a-chip devices, also known as microfluidic arrays, are commonly used to sort tiny samples by size, shape or composition, but the minuscule forces at work at such a small magnitude are difficult to measure. To solve this small problem, the Johns Hopkins engineers decided to think big.

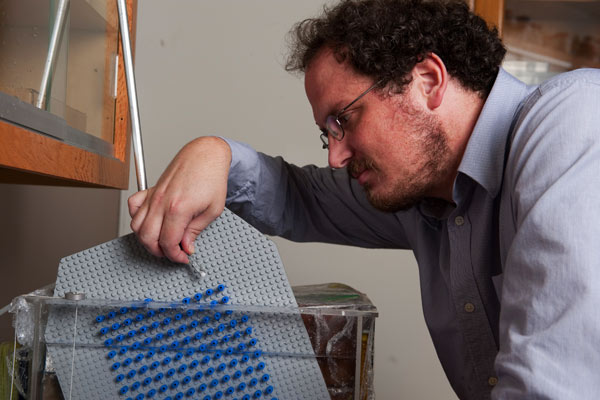

German Drazer, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, uses a LEGO board to study the way particles behave in a microfluidic device.

Led by Joelle Frechette and German Drazer, both assistant professors of chemical and biomolecular engineering in the Whiting School of Engineering, the team used beads just a few millimeters in diameter, an aquarium filled with goopy glycerol and the LEGO pieces arranged on a LEGO board to unlock mysteries occurring at the micro- or nanoscale level. Their observations could offer clues on how to improve the design and fabrication of lab-on-a-chip technology. Their study concerning this technique was published in the Aug. 14 issue of Physical Review Letters.

The idea for this project comes from the concept of “dimensional analysis,” in which a process is studied at a different size and time scale while keeping the governing principles the same.

“Microfluidic arrays are like miniature chemical plants,” Frechette said. “One of the key components of these devices is the ability to separate one type of constituent from another. We investigated a microfluidic separation method that we suspected would remain the same when you scale it up from micrometers or nanometers to something as large as the size of billiard balls.”

With this goal in mind, Frechette and Drazer constructed an array using cylindrical LEGO pegs stacked two high and arranged in rows and columns on a LEGO board to create a lattice of obstacles. The board was attached to a Plexiglas sheet to improve its stiffness and pressed up against one wall of a Plexiglas tank filled with glycerol. Stainless steel balls of three different sizes, as well as plastic balls, were manually released from the top of the array; their paths to the bottom were tracked and timed with a camera.

The entire setup, Drazer said, cost a few hundred dollars and could easily be replicated as a science fair experiment.

Graduate students Manuel Balvin and Tara Iracki, and undergraduate Eunkyung Sohn, all from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, performed multiple trials using each type of bead. They progressively rotated the board, increasing the relative angle between gravity and the columns of the array (that is, altering the forcing angle). In doing so, they saw that the large particles did not move through the array in a diffuse or random manner as their small counterparts usually did in a microfluidic array. Instead, their paths were deterministic, meaning that they could be predicted with precision, Drazer said.

The researchers also noticed that the path followed by the balls was periodic once the balls were in motion and coincided with the direction of the lattice. As the forcing angle increased, some of the balls tended to shift over one, two, three or as many as four pegs before continuing their vertical fall.

“Our experiment shows that if you know one single parameter—a measure of the asymmetry in the motion of a particle around a single obstacle—you can predict the path that particles will follow in a microfluidic array at any forcing angle, simply by doing geometry,” Drazer said.

The fact that the balls moved in the same direction inside the array for different forcing angles is referred to as phase locking. If the array were to be scaled down to micro- or nanosize, the researchers said they would expect these phenomena still to be present and even increase depending on the factors such as the unavoidable irregularities of particle size or surface roughness.

“There are forces present between a particle and an obstacle when they get really close to each other which are present whether the system is at the micro- or nanoscale or as large as the LEGO board,” Frechette said. “In this separation method, the periodic arrangement of the obstacles allows the small effect of these forces to accumulate, and amplify, which we suspect is the mechanism for particle separation.”

This principle could be applied to the design of micro- or nanofluidic arrays, she added, so that they could be fabricated to “sort particles that had a different roughness, different charge or different size. They should follow a different path in an array and could be collected separately.”

Phase locking is likely to become less important, Drazer cautioned, as the number of particles in solution becomes more concentrated. “Next,” he said, “we have to look at how concentrated your suspension can be before this principle is destroyed by particle-particle interactions.”

Drazer and Frechette are both affiliated faculty members of the Johns Hopkins Institute for NanoBioTechnology. The research was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund.

Related Web sites: