February 1, 2010

Stressed nanomaterials display unexpected movement

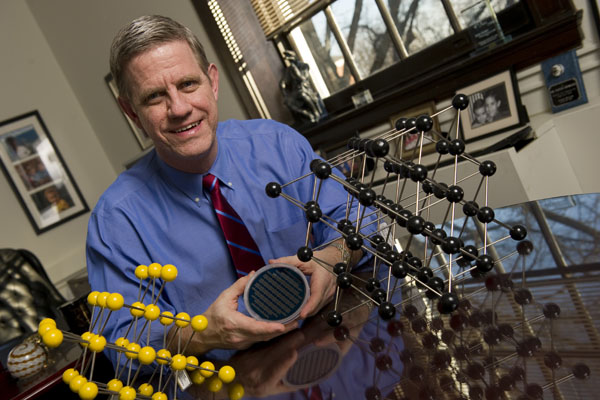

Kevin Hemker, seated between models representing how atoms are packed within an individual grain in a material, holds a silicon wafer onto which nanocrystalline aluminum thin film specimens have been deposited. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

Researchers have discovered that, under the right conditions, newly developed nanocrystalline materials exhibit surprising activity in the tiny spaces between the geometric clusters of atoms called nanocrystals, from which they are made.

This finding, detailed recently in the journal Science, is important because these nanomaterials are becoming more ubiquitous in the fabrication of microdevices and integrated circuits. Movement in the atomic realm can affect the mechanical properties of these futuristic materials—making them more flexible and less brittle, for example—and may alter the material’s lifespan.

“As we make smaller and smaller devices, we’ve been using more nanocrystalline materials that have much smaller crystallites—what materials scientists call grains—and are believed to be much stronger,” said Kevin Hemker, professor and chair of Mechanical Engineering in Johns Hopkins’ Whiting School of Engineering and senior author of the Science article. “But we have to understand more about how these new types of metal and ceramic components behave, compared to traditional materials. How do we predict their reliability? How might these materials deform when they are subjected to stress?”

The experiments conducted by a former undergraduate research assistant and supervised by Hemker focused on what happens in regions called grain boundaries. A grain or crystallite is a tiny cluster of atoms arranged in an orderly three-dimensional pattern. The irregular space or interface between two grains with different geometric orientations is called the grain boundary. Grain boundaries can contribute to a material’s strength and help it resist plastic deformation, a permanent change of shape. Nanomaterials are believed to be stronger than traditional metals and ceramics because they possess smaller grains and, as a result, have more grain boundaries.

Most scientists have been taught that these grain boundaries do not move, a characteristic that helps the material resist deformation. But when Hemker and his colleagues performed experiments on nanocrystalline aluminum thin films, applying a type of force called shear stress, they found an unexpected result. “We saw that the grains had grown bigger, which can only occur if the boundaries move,” he said, “and the most surprising part of our observation was that it was shear stress that had caused the boundaries to move.

“The original view,” he said, “was that these boundaries were like the walls inside of a house. These walls and the rooms they create don’t change size; the only activity is by people moving around inside the room. But our experiments showed that in these nanomaterials, when you apply a particular type of force, the rooms do change size because the walls actually move.”

The discovery has implications for those who use thin films and other nanomaterials to make integrated circuits and microelectromechanical systems, commonly called MEMS. The boundary movement shown by Hemker and his colleagues means that the nanomaterials used in these products likely possess more plasticity, higher reliability and less brittleness, but also reduced strength.

“As we move toward making things at much smaller sizes, we need to take into account how activity at the atomic level affects the mechanical properties of the material,” Hemker said. “This knowledge can help the microdevice makers decide on the proper size for their components and can lead to better predictions about how long their products will last.”

The journal article describing this discovery was inspired by a Johns Hopkins master’s thesis produced by Tim Rupert, then a combined bachelor’s/master’s degree student in mechanical engineering. Rupert, who is now a doctoral student at MIT, is lead author of the Science piece. Along with Hemker, the co-authors are Daniel Gianola, a former doctoral student and postdoctoral fellow in Hemker’s lab who is now an assistant professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Pennsylvania; and Y. Gan, of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Funding for the research was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.

Related Web sites