March 1, 2010

Satellites, rockets and more

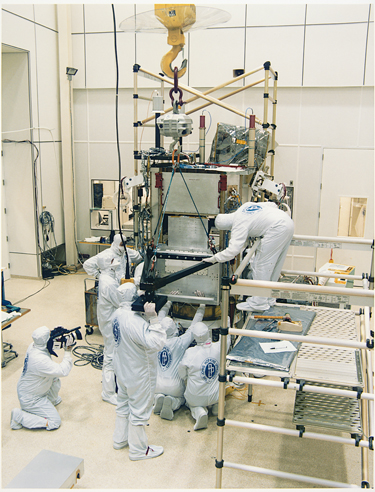

A videographer documents work being done in a cleanroom at APL during assembly of the TIMED spacecraft. The satellite was launched in 2001. Photo: Applied Physics Laboratory

On Sept. 17, 1959, a little heralded Thor Able rocket launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida. Perched atop the rocket was Transit 1A, a satellite designed by scientists and engineers at Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Laboratory that the U.S. Navy hoped would provide accurate location information to ballistic missile submarines and be used as a general navigation system.

Twenty-five minutes into the flight, Transit 1A plummeted into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Ireland. The rocket booster’s third stage had failed to fire.

A colossal disappointment? Not quite. The satellite, even on its brief journey, had gathered enough data to prove to APL and its Navy sponsors that the project was worthwhile. With the launch, the APL space program was effectively born.

APL proceeded with development of Transit, also known as NAVSAT (for Navy Navigation Satellite System), and a year later it became the first satellite navigation system to be used operationally, and an important tool to study the Earth’s atmosphere for years to come.

The story of this little satellite that could and its descendants— and the many successes and some stumbles that followed—are chronicled in a new book titled Transit to Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Space Research at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. The book, co-authored by the Sheridan Libraries’ Mame Warren and APL’s Helen Worth, contains oral histories from more than 50 people who contributed to and shaped the history of the Lab’s space program, including such giants as Stamatios “Tom” Krimigis, the godfather of robotic spacecraft; Richard Kershner, first head of the Space Department; and Michael Griffin, a later Space Department head and NASA administrator from 2005 to 2009.

The book was commissioned to celebrate the 50th anniversary of space research at APL.

No stranger to Johns Hopkins history, Warren, director of Hopkins History Enterprises for the Sheridan Libraries, authored Johns Hopkins: Knowledge for the World: 1876–2001 for the university’s 125th anniversary and Our Shared Legacy: Nursing Education at Johns Hopkins, 1889–2006. Worth joined APL 23 years ago and now directs its Office of Communications and Public Affairs.

In large part, Transit to Tomorrow tells the story of APL’s pioneering role in the space age and how space technology has evolved over the past 50 years.

The Lab has made many notable contributions.

In addition to the first satellite navigation system, APL can take credit for the first picture from space, which provided the first absolute evidence of the curvature of the Earth; the first spacecraft to land on an asteroid; and the design of the new generation of smaller, more efficient spacecraft that predate NASA’s Discovery Program.

The Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging spacecraft, known as MESSENGER, is just one example of APL’s cost-effective approach to space exploration. MESSENGER launched in 2004 and will conduct an in-depth study of Mercury, the sun’s closest neighbor and the least explored of the terrestrial planets. Its voyage has already included three flybys of Mercury, in 2008 and 2009, with a yearlong orbit of the planet set to begin in March 2011.

Since its beginning, APL’s Space Department has produced spaceflight hardware and software systems, and conducted space science and engineering for both civilian and military customers. To date, it has successfully designed, built and operated more than 64 spacecraft and 200 instruments. It currently has approximately 700 staff members.

The department’s expertise in space science research involves solar-terrestrial physics, astrophysics, planetary magnetospheres, planetary geology, solar physics and related space research such as oceanography and atmospheric and ionospheric physics.

John Sommerer, head of the Space Department, said that the book, in addition to being “a great read,” offers a unique eyewitness report from the pioneers of a new era in human exploration.

“It’s a rare opportunity to capture some of the excitement from the opening of an era. In another 10 years, such a book would probably not be possible. Ten years earlier, it would be harder to have a clear perspective on the significance of the events,” Sommerer said. “I think that Mame and Helen were brilliant in creating a narrative from such a large chorus of voices, without long monologues from any one person.”

Sommerer said that APL certainly joined the space age with a bang.

“The invention of satellite navigation solved a huge problem in national security and also launched DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) on its illustrious trajectory,” he said.

Transit’s history can be traced back to the launch of Sputnik on Oct. 4, 1957. Days after the launch, APL scientists George Weiffenbach and William Guier were able to ascertain Sputnik’s orbit by analyzing the Doppler shift of its radio signals during a single pass. Frank McClure, the chairman of APL’s Research Center at the time, suggested that if the satellite’s position were known and predictable, the Doppler shift could be used to locate a receiver on Earth, a revelation that would eventually lead to navigation by satellite and to today’s GPS systems.

On the Lab’s civilian side, Sommerer said that the NEAR mission was “a paradigm breaker” for space exploration. APL made space history in 2000–2001 with NEAR, or Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous, which was the first spacecraft to orbit and then land on an asteroid.

“NEAR launched APL onto an interplanetary trajectory,” he said. “There are really only three institutions in the country that can perform the whole science-to-mission concept: mission development, to mission operations, to science return, to new science questions cycle. The other two, JPL and Goddard, are about a factor of 10 bigger than APL Space.”

Worth said that although the book was written with an internal audience in mind, the stories are for anyone with an interest in space-age history.

“APL has always kind of flown under the radar. We’re not out for publicity by the nature of the work that we do,” Worth said. “But we were instrumental in the beginning of the space age and all along its path. That story was not being told, and we figured if we don’t tell it now, much of it would be lost. People are not going to be around forever, and we still have a lot of people who were there at the beginning. This was the perfect time to do it.”

Warren said that work on the book technically began two years ago, although for her it began nearly 10 years ago, when she was researching Knowledge for the World and interviewed Alexander Kossiakoff, guided missile pioneer and former APL director.

“I’m not sure if that gave me a full leg up. I sort of crawled into this project and learned as I went, and it was wonderful,” she said. “One of the earliest people I spoke to was Bill Guier, who was one of the two guys who originally recorded the sound of Sputnik and figured out what you were listening to was the Doppler effect.

“Here I was talking to the guy who had the initial kernel of an idea that is now part of everyday life,” Warren said. “That’s part of the excitement of the entire space program: how it has impacted our everyday life in so many ways.”

As for what lies ahead for the APL Space Department, Sommerer said that predictions are hard, but he has a good sense of where things are headed. One of the next big projects for APL is to literally fly a spacecraft into the sun’s outer atmosphere, to “touch the sun.”

“This is a prize that space scientists have looked forward to for 50 years, and APL is the institution that, through internal investment and risk reduction via NASA study and technology development funding, finally convinced NASA that this could be done,” he said. “We started on Phase A of the Solar Probe Plus program this year and expect to launch this audacious mission before 2018. Lots of other great things are going to happen in the interim, like going into orbit around Mercury for the first time about a year from now; conducting the Radiation Belt Storm Probe mission, starting in 2012, to study the Van Allen Belts; flying by Pluto in 2015; and building APL’s smallest satellite ever to support the U.S. military.”

Sounds like fodder for another book.

To read Transit to Tomorrow online or purchase the book for $20, go to http://space50 .jhuapl.edu.