July 6, 2010

New clues in north suggest wet era on early Mars was global

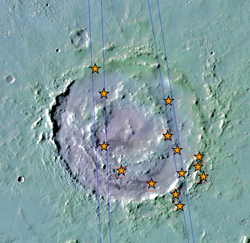

Lyot Crater is one of at least nine craters in the northern lowlands of Mars with exposures of hydrated minerals (indicated by stars) detected from orbit, according to a June 25 report. Photo: NASA / ESA / JPL-Caltech / The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / IAS

A phase in the early history of Mars with conditions favorable to life occurred globally rather than just in the south, new findings from the north suggest.

Southern and northern Mars differ in many ways, so the extent to which they shared ancient environments has been open to question.

In recent years, the European Space Agency’s Mars Express Orbiter and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have found clay minerals that are signatures of a wet environment at thousands of sites in Mars’ southern highlands, where rocks on or near the surface are about 4 billion years old. Until now, no sites with those minerals had been reported in the northern lowlands, where younger volcanic activity has buried the older surface more deeply.

French and American researchers reported June 25 in the journal Science that some large craters penetrating younger, overlying rocks in the northern lowlands expose similar mineral clues to ancient wet conditions.

“We can now say that the planet was altered on a global scale by liquid water about 4 billion years ago,” said the report’s lead author, John Carter, of the University of Paris.

Other types of evidence about liquid water in later epochs on Mars tend to point to shorter durations of wet conditions or water that was more acidic or salty.

The researchers used the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, or CRISM—an instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter—to check 91 craters in the northern lowlands. In at least nine, they found on the surface, or under ground, clays and claylike minerals called phyllosilicates or other hydrated silicates that form in wet environments.

Earlier observations with the OMEGA spectrometer on Mars Express had tentatively detected phyllosilicates in a few northern plains craters, but the deposits are small, and CRISM can make focused observations on smaller areas than OMEGA.

“We needed the better spatial resolution to confirm the identifications,” Carter said. “The two instruments have different strengths, so there is a great advantage to using both.”

CRISM principal investigator Scott Murchie, of Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Laboratory and a co-author of the new report, said that the findings aid interpretation of when the wet environments on ancient Mars existed relative to some other important steps in the planet’s early history.

The prevailing theory for how the northern part of the planet came to have a much lower elevation than the southern highlands is that a giant object slammed obliquely into northern Mars, turning nearly half the planet’s surface into the solar system’s largest impact crater. The new findings suggest that at least part of the wet period favorable to life extended into the time between that giant impact and when volcanic and other rocks formed an overlying mantle.

“That large impact would have eliminated any evidence for the surface environment in the north that preceded the impact,” Murchie said. “It must have happened well before the end of the wet period.”

The report’s other authors are Francois Poulet and OMEGA principal investigator Jean-Pierre Bibring, both of the University of Paris.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology, manages the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter for NASA. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory provided and operates CRISM, one of six instruments on that orbiter.

Related websites