July 19, 2010

‘Hubble repairman’ now a Johns Hopkins research professor

John Grunsfeld joins Krieger School of Arts & Sciences

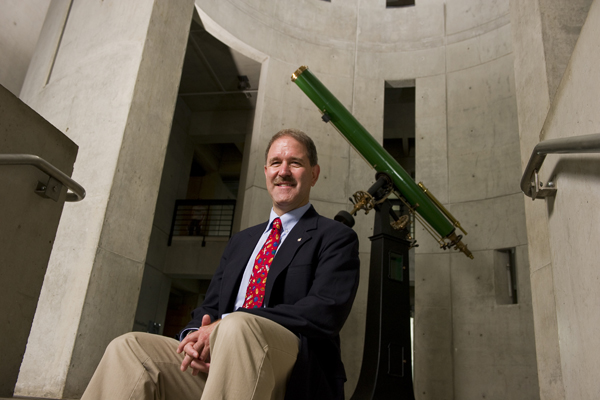

After more than 800 hours of floating in space, former NASA astronaut John Grunsfeld settles down in the Bloomberg Center for Physics and Astronomy. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

NASA astronaut John Grunsfeld has walked in space eight times and logged more than 800 hours floating in that deep, dark void over the course of five space flights, including three to service the Hubble Space Telescope. Now, he is about to explore a new frontier: The Johns Hopkins University.

On July 1, the man nicknamed “the Hubble repairman” became a research professor in the Henry A. Rowland Department of Physics and Astronomy in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. While at Johns Hopkins, Grunsfeld, who is deputy director at the nearby Space Telescope Science Institute, will continue his research in astrophysics and the development of new technology and systems for space astronomy.

“Johns Hopkins University and the Department of Physics and Astronomy have a rich heritage of research at the forefront of experimental astrophysics, including the Hubble Space Telescope. I’m thrilled to be joining the university community and look forward to contributing to the research mission and to participating in the exciting interdisciplinary efforts at Johns Hopkins. With the great team at Johns Hopkins, not even the sky is the limit,” Grunsfeld said.

Astrophysicists at Johns Hopkins have been involved with the Hubble Space Telescope since its launch in 1990. Researchers here are part of the science and engineering team for the Advanced Camera for Surveys, which was installed in the Hubble during the Columbia mission in 2002, and researchers at both the Krieger School and APL use data gathered by the instrument. The Space Telescope Science Institute, which serves as space operations headquarters for the Hubble, is located on Johns Hopkins’ Homewood campus, and there is a long history of collaboration between researchers there and at the Krieger School.

Daniel Reich, chair of Physics and Astronomy, said he is “thrilled” to have Grunsfeld join the Johns Hopkins team and that the former astronaut is already involved in collaborations with faculty members on high-energy astrophysics projects.

“Dr. Grunsfeld’s expertise with space flight will be a great asset as we seek to compete for new space-based astrophysics missions in the near future,” Reich said. “Of equal importance to us is his potential impact on Johns Hopkins’ educational mission. Dr. Grunsfeld has done extensive work for NASA in the area of science education for the general public, and he is an extraordinarily engaging public speaker. He gave a fantastic guest lecture this spring in one of our undergraduate classes, and we are very excited about finding additional opportunities for him to engage with our students.”

Considered one of the top space scientists in the nation, Grunsfeld is known as much for his colorful personality as he is for his work in space. The grandson of the man who designed Chicago’s Adler Planetarium, Ernest Grunsfeld Jr., the Windy City native decided at age 6 that he wanted to be an astronaut when he grew up. While studying for his bachelor’s in physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Grunsfeld earned $4 an hour and dreamed of going into space while working the graveyard shift in the control room of the Third Small Astronomy Satellite (SAS-3), which was designed and built at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

After earning his master’s in physics at the University of Chicago, he traveled to Japan, where he worked with University of Tokyo astronomer Minoru Oda. He later returned to the University of Chicago to earn his doctorate in physics, married and took a position at the California Institute of Technology.

In 1992, Grunsfeld received training at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, qualifying as a mission specialist. His dream of going into space came true when he was chosen for the space shuttle Endeavour, which launched March 2, 1995, from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. During the 399-hour mission, Grunsfeld and the crew used three ultraviolet telescopes to study the far ultraviolet spectra of faint astronomical objects and the polarization of ultraviolet light coming from hot stars and distant galaxies.

Two years later, in January 1997, Grunsfeld served as flight engineer for the 10-day space shuttle Atlantis mission, which was the fifth ever to dock at Russia’s Mir Space Station. During that mission, more than three tons of food, water, equipment and supplies were moved back and forth between the two spacecraft. While on board the Atlantis, Grunsfeld amused NPR listeners by calling in to the popular car repair show Car Talk, hosted by Tom and Ray Magliozzi. While a student at MIT, he had taken his 1966 Sunbeam Alpine to the celebrity mechanics for repairs, and during the space flight seemed an ideal time to reconnect.

What followed were three missions to repair the Hubble Space Telescope, including the shuttle Discovery in 1999, the Columbia in 2002 and, finally, Atlantis again in May 2009. For that mission, Grunsfeld was the lead mission specialist and headed the planning for all the spacewalks involved in the spectacularly successful repairs and upgrades carried out during that trip. Grunsfeld installed two new instruments—the Wide Field Camera 3 and the Cosmic Origins Spectograph—on the Hubble, and helped replace a guidance sensor, six new gyroscopes and two battery unit modules, all aimed at allowing the telescope to continue to function until 2014.

“John has the enviable experience of being one of the few humans ever to bring the Hubble Space Telescope to the apex of its scientific capability. We are indebted to him for his perseverance, skill and unswerving dedication in helping us usher in a bold new decade of exciting astronomical discoveries,” said Matt Mountain, director of the Space Telescope Science Institute.

In addition to his adventures in space, in 2003 and 2004 Grunsfeld served as the NASA chief scientist at NASA Headquarters, where he helped develop the President’s Vision for Space Exploration.

Grunsfeld’s adventuring has not been limited to outer space. In 2002, the Hubble repairman and NASA consultant Howard Donner, a physician, tackled North America’s highest peak—Mount McKinley—as part of a study on how altitude affects body temperature. The research required the men to swallow pill-sized thermometers (invented by researchers at Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Laboratory and NASA), which measured their temperature during the trek. The pair, whose efforts were featured in a PBS NOVA episode titled “Deadly Ascent,” reached 17,200 feet before having to turn back due to altitude sickness. Disappointed but undaunted, two years later Grunsfeld became the only American astronaut to reach the summit of Mount McKinley, leading a team of other NASA explorers.