August 16, 2010

Materials scientist seeks dwarfism clues in cell’s membrane

Federal stimulus funding supports nontradtional research into genetic defect

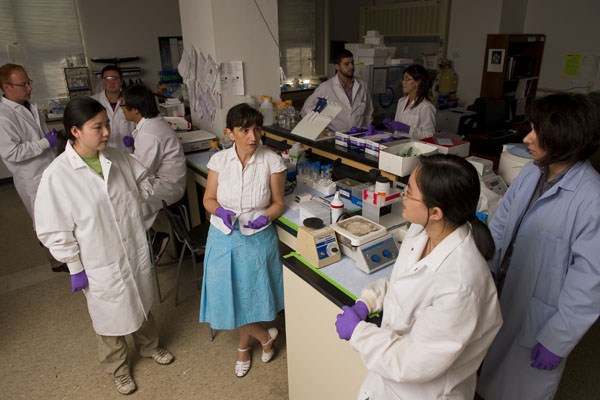

Kalina Hristova in her lab with students, clockwise from left, Lirong Chen, Jesse Placone, Juan Cruz, Fenghao Chen, David Rezzo, Sandra Carolina Agudelo, Sarvenaz Sarabipour and Lijuan He. Photo: Will Kir/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

This is part of an occasional series on Johns Hopkins research funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. If you have a study you would like to be considered for inclusion, contact Lisa De Nike at lde@jhu

.edu.

Achondroplasia, a common form of dwarfism, is caused by a genetic mutation: A single incorrect building block in a strand of DNA produces a defective protein that disrupts normal growth. If a scientist could figure out precisely how this errant protein causes trouble, then a solution might be found.

Sounds like a job for a biologist.

Think again. The person who cracks this mutation mystery might just be a Johns Hopkins engineer who works with cell membranes.

Kalina Hristova, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, has spent more than five years in a nontraditional effort to understand how that tiny DNA error leads to dwarfism. Hristova, an expert in the field of membrane biophysics, has focused her research on the thin protective covering that surrounds human cells, the plasma membrane; for this project, she is studying the activity of proteins that reside in this membrane, among which is the one linked to dwarfism.

A biologist might attack this puzzle by growing cells in a dish or conducting experiments with lab animals. Hristova, supported by a federal stimulus grant, instead has been using engineering tactics to determine how the protein may be wreaking havoc. Her lab has developed new tools and techniques that allow her to take pictures and make measurements that reveal how the rogue protein is behaving in the cell membrane. Her team’s goal is to generate exact numbers that will yield clues about how the protein causes the cells to take a wrong turn.

“Unlike the biologists, we are not investigating what will happen to the cell in 20 days,” she said. “We are looking at the initial events occurring in the cell membrane, the way proteins first interact there. As engineers, we have to strip down the system and simplify it so that we can see how it works. We are looking at the physics not the biology.”

For her project, called “Seeking the Physical Basis of Achondroplasia,” Hristova has received a $27,000 federal stimulus grant for lab equipment, which supplements her five-year grant of approximately $1 million from the National Institutes of Health. Her award is among the 424 stimulus-funded research grants and supplements totaling more than $200 million that Johns Hopkins has garnered since Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, bestowing the NIH and the National Science Foundation with $12.4 billion in extra money to underwrite research grants by September 2010.

Achondroplasia, the focus of Hristova’s grant, is the most common form of short-limbed dwarfism, occurring in one in 15,000 to 40,000 newborns, according to the National Institutes of Health. The condition results from a mutated FGFR3 gene. In some cases, this mutation is passed down by at least one parent. But about 80 percent of those with achondroplasia have average-size parents and develop the condition because a new mutation occurs. This defective gene produces proteins that send “stop” signals, halting the growth of cartilage that makes room for normal-size long bones of the arms and legs.

Hristova cautions that no “cure” for achondroplasia exists and that her research is unlikely to produce one in the near future. She describes her work as basic research that could lay the groundwork for future treatment or prevention of achondroplasia. “Finding the cause of this condition is a very hard problem because the first thing you need to do is to understand what’s happening at the molecular level, what these proteins are actually doing,” she said. “Before you can solve a problem, you need to know what’s causing it.”

The proteins Hristova is examining are tiny threads of amino acids embedded in the cell membrane, with one end extending inside the cell and the other wriggling outside. This arrangement allows the protein to gather information outside the cell and send messages to the nucleus, or control center, inside the cell. These messages provide instructions to the cell, including telling it whether or not to grow.

To find out how this process goes awry in people with dwarfism, Hristova is looking at how the mutated protein is embedded within the membrane, compared to the proteins of people who grow normally. Does one type stick farther inside or outside the cell? She also is trying to find out whether the growth disorder is related to the chemical and mechanical ways that the mutated proteins “talk” to other proteins in the cell membrane.

To conduct these studies, Hristova and her team coax cells into making the protein, then “trick” the cells into giving up their membranes with the proteins still embedded in the material. The researchers then use a confocal microscope to gather information about the mutated proteins in these membrane segments without the constant turnover of molecules that occurs in an intact living cell. Her team also works with National Institute of Standards and Technology scientists in using a technology called neutron diffraction to collect images that show where the proteins are situated with respect to the membrane’s surface. “We are using materials science techniques to conduct innovative research into why this form of dwarfism is occurring,” Hristova said.

Hristova, whose parents are scientists, said that her entry into the field of membrane biophysics occurred “sort of by chance.” In her native Bulgaria, while earning her undergraduate and master’s degrees in physics, she became interested in biophysics. At one point, an instructor assigned her work on membranes, and she quickly embraced this area of research.

She came to the United States to pursue a doctorate in engineering and materials science at Duke, and then further honed her research skills as a postdoctoral fellow at UC Irvine. In 2001, she joined the faculty of the Whiting School of Engineering at Johns Hopkins, where she specializes in membrane biophysics and biomolecular materials and is an affiliate of the Institute for NanoBioTechnology. In 2007, Hristova received the Biophysical Society’s Margaret Oakley Dayhoff award for “her extraordinary and outstanding scientific achievements in biophysics research.”

Her interest in the dwarfism mutation originated years ago when a physician talked to her about the problem and sparked her interest in finding a solution through engineering techniques. In recent years she has presented her findings at scientific conferences attended mainly by researchers who continue to study the disorder with the tools of a biologist. “Eventually, sometime in the future, both approaches will come together as we work toward a basic understanding of what causes achondroplasia,” Hristova said. “Then someone will come up with a treatment.”

Related websites

Johns Hopkins Department of Materials Science and Engineering