October 18, 2010

Whiting School of Engineering students take a Jhpiego field trip

Aspiring biomedical engineers test ideas in India, Nepal, Tanzania

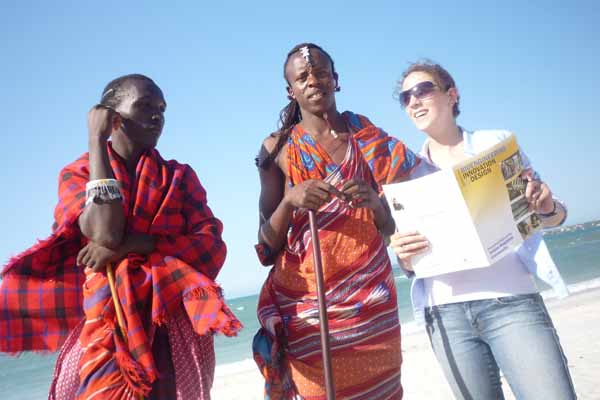

Sherri Hall, a graduate student in the Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design, with CBID brochure in hand, poses with two Maasai tribesmen on the shores of Tanzania. Photo: Shishira Nagesh

Johns Hopkins University engineering students are helping design biomedical solutions for health care problems in the developing world as part of a unique partnership with Jhpiego, a global health nonprofit and Johns Hopkins affiliate working to prevent needless deaths of women and families.

The 15 students, all enrolled in the one-year graduate program of the Whiting School of Engineering’s Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design, spent two weeks this summer in field placements in India, Nepal and Tanzania, where they saw up close the health challenges facing women and researched the compatibility of proposed biomedical solutions to eclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage and other reproductive-health issues. They also got a feel for the impact that societal and cultural realities can have on delivery of health services.

Though James Waring, 24, of Yorktown, Va., had lived in Belgium and France, working in the developing world was new to him, he said. “We are sort of wrapped up in a bubble of our own. The challenges [there] are completely different,” he said.

The overseas rotations were a first for Waring and the other aspiring biomedical engineers, an outgrowth of a project begun 18 months ago with JHU undergraduate and graduate students and Jhpiego, which is committed to moving research and innovation in global health out into the field.

Harshad Sanghvi, Jhpiego’s medical director, said that after visiting the Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design, he saw the potential for collaboration with students.

“What we are trying to do is to develop extremely affordable technologies that are custom-designed for taking care closer to where women are having problems, often far away from any formal health care setting, and to ensure that cost and a woman’s ability to reach hospitals are not barriers to accessing lifesaving health care,” Sanghvi said. “Jhpiego’s knowledge of these needs developed over 35 years of work in the most difficult places in the world, combined with the ingenuity of bright young engineering graduate students, is a powerful combination to make devices that could make transformational change. I saw in this group of JHU students the innovators of tomorrow.”

Joining with the engineering school’s Soumyadipta Acharya, an assistant research professor, Sanghvi issued five design challenges whose goal was to develop low-cost solutions to health care problems that contribute to high maternal mortality rates in many parts of the world. Acharya, in turn, proposed to Sanghvi “that our students should get some field experiences, or these devices aren’t going to make sense,” he said. “A minute of immersion in the field is worth 10 pages you can read. Words can’t describe it.”

The Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design offered all the students in the one-year master’s program the opportunity to participate in a field placement, though it was not a requirement. The Whiting School covered most of the cost of the trips and used grants and gifts for the rest; students paid for their meals and personal expenses. All 15 chose to go. As part of their curriculum, the students take a course each semester on global health.

In a recent presentation to Jhpiego staff, the students described their experiences, saying that their interactions with policymakers, clinicians, nurses, midwives and health workers helped them understand the potential impact of simple yet effective innovations in rural clinics and remote areas.

Students who visited India said they saw the difficulty in managing the third stage of labor with nearly a dozen pregnant women in one room. Partographs were being used as a record-keeping tool rather than to help make decisions. Mary O’Grady and her fellow students approached the problem from a new perspective. With many patients to care for at the same time, measurements on the Partograph took a lot of time and were not being done. “We asked, ‘What if the Partograph did it for you?’” said O’Grady, 22, of Anchorage, Alaska.

In Tanzania and India, students discussed possible plans to develop syringes that are disposable. Some providers shared concerns over costs, while others worried about possible reuse of the syringes. “Articulating desired and absolute needs was hard,” said Shishira Nagesh, 24, of Bangalore, India. “The concept of having a ‘biomedical engineering’ [program] was something very new in the places we visited. So it was hard to get across our purpose there.”

Students had to explain that they were at the start of a project to design new and innovative biomedical tools, not participating in clinical trials, she said.

In Nepal, the students researched what level of care would be most appropriate to introduce the intrauterine tamponade, a device used to stop postpartum hemorrhage. While a district hospital made sense, distribution of a tamponade by a skilled birth attendant in a basic care setting might have greater impact. They also learned that a tamponade would have to cost less than $7 to be used widely in the Himalayan nation.

While working in Kathmandu, Matthew Means, 22, of Punxsutawney, Pa., took stock of infection prevention measures. In Nepal, except when you go into a sterile operating theater, he said, supplies are very scarce. “At Hopkins there is a hand sanitizer on every wall and outside every door,” Means said.

Max Budyansky, 22, of West Hartford, Conn., said he admired the resourcefulness on display at an Indian hospital.

“The Kasturba Hospital had a fraction of the technology and equipment [compared to U.S. hospitals]. But the doctors and staff were so dedicated to the patients, so highly trained. They have virtually the same outcomes, the same infection rates, [and] they reuse and innovate on equipment they lack,” he said. “An excess IV line became a drain; gloves were autoclaved, sterilized and reused. Things were made so cost-efficient.”

Sean Monagle, who had begun work on his project as an undergraduate, had the experience of actually field-testing the protein pen, a simple device to screen women for the effects of preeclampsia, a condition in some 10 percent of pregnancies characterized by high blood pressure that if left undetected can advance to life-threatening eclampsia.

Until his trip, Monagle, 22, of Jacksonville, Fla., had tested the protein pen only with artificial urine. But in Nepal, in a study led by principal investigator Sanghvi, he was assigned to a crowded maternity hospital, where he had access to scores of potential samples. Jhpiego has been looking for very low-cost solutions to make detection of preeclampsia possible at home and in the community.

“I had only been testing four to five samples at a time [in Baltimore]. Here we finally managed to get a couple of hundred,” Monagle said. “I continued to tweak the reagent over the summer. It was nice to be able to go out and do a big sample like this. It was also productive seeing how many people actually loved the idea.”

When word got out about his easy-to-use screening agent, Monagle said, members of the medical community wanted to have him test the device at their facilities, too. “I’d been working on it [with Jhpiego] for two years, and I never imagined how big an impact it could have. I never imagined that people over here wanted a test like this,” Monagle said. “Ever since I started working on this project, I loved the concept and the idea. One of the reasons was because of the potential for application.”

The students returned to their labs equipped with a more thorough view of the biomedical needs of the developing world, a realistic sense of the commercial potential of the global marketplace and a newfound confidence that they can innovate and deliver.

This month, the U.S. Agency for International Development announced that it would give one of its first Innovation Venture Awards to Jhpiego for one of the projects begun with the Whiting students. The $100,000 award is for refining the design of a simple, reliable and low-cost screening test for preeclampsia among pregnant women in low-resource settings.