January 24, 2011

Libraries in the information age

Dean Winston Tabb on our electronic future and our changing facilities

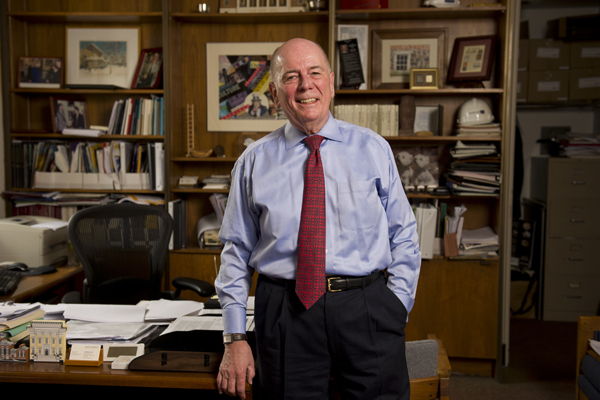

As Sheridan Dean of University Libraries, Winston Tabb leads and coordinates the university’s entire system of libraries. He also heads up JHU’s two museums. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

Winston Tabb likes a challenge, and he’s OK with change.

Tabb became Sheridan Dean of University Libraries and director of the Sheridan Libraries in September 2002. Since his arrival at Johns Hopkins, he has accepted additional assignments, as dean of the university’s museums and as head of a number of arts initiatives.

As Sheridan Dean, Tabb directs the integration of new information technologies throughout Johns Hopkins’ libraries and serves as head of the University Libraries Council, which leads and coordinates the university’s entire system of libraries: the Welch Medical Library and its satellite facilities; SAIS’ Mason Library; Peabody’s Friedheim Library; libraries at the Johns Hopkins regional campuses and centers for part-time studies in Washington, D.C.; Rockville, Md.; Columbia, Md.; and downtown Baltimore; and the Sheridan Libraries.

The Sheridan Libraries include the Milton S. Eisenhower Library on the Homewood campus; the George Peabody Library on Mount Vernon Place in Baltimore; the John Work Garrett Library at Evergreen Museum & Library; and the Hutzler Undergraduate Reading Room in Homewood’s Gilman Hall. In July 2012, a new facility—the 42,000-square-foot Brody Learning Commons, which is intended for technology-driven and collaborative learning—will open next to the Milton S. Eisenhower Library.

As dean of university museums, Tabb oversees Homewood Museum and Evergreen Museum & Library, both of which are open to the public for tours, exhibitions, concerts and other events. The two museums are also increasingly involved in the academic life of the university.

In July 2006, Tabb was appointed to a two-year term as vice provost for the arts. In that position, he chaired the Homewood Arts Task Force and coordinated efforts to extend its work across the university. Tabb also was charged with developing a strategy for funding arts initiatives and with building relationships with arts organizations in the greater Baltimore community.

Before coming to Johns Hopkins, Tabb was with the Library of Congress for 30 years in a variety of roles. As associate librarian, he managed 53 of the Library of Congress’ divisions and offices.

A native of Tulsa, Okla., Tabb graduated from the Oklahoma Baptist University and went to Harvard University as a Woodrow Wilson fellow, earning a master’s degree before serving in the U.S. Army as an instructor of English in Thailand.

The Gazette recently sat down with Tabb to discuss the future of a university library system in an electronic information world.

Q: You’ve added some hats since you arrived here, and one can say you now oversee a vast information empire. How do you make it all work?

A: I have lots of good help; that is the main thing. I bring a lot of energy to the job, and I like doing new things. There’s always something new to do.

There are also more things in common in terms of libraries and museums than people might think. I don’t see them as two different things, but two parts of one whole. That is the way I approach it. I’ve wanted to get our museums more integrated into the academic mission of the university. The library has always had that.

Q: The library system is much more than the Milton S. Eisenhower Library that we’re sitting in today. How much involvement do you have with the facilities at other campuses?

A: Quite a lot. We have an organization called the University Libraries Council, which I chair, and it comprises the five heads of the library systems within Johns Hopkins: the Sheridan Libraries, the Welch Medical Library, Peabody’s Friedheim Library, APL’s library and SAIS’ libraries, not only in Washington but in Bologna and Nanjing. The five of us meet four times a year. We do a lot of things together, and it’s working really well.

One of the first things we did was create one library automation system so that anyone who goes online to see what books are in the libraries at Johns Hopkins now can find all the books in one place. When I arrived here, there were three different systems.

The second step, and probably the single most important thing we’ve done, was to start buying all our electronic resources as one university. Before, we had three entities bargaining for prices to satisfy their customer bases. Now, we do all of this by having one person buy for everyone. The publishers have agreed to treat Johns Hopkins as one entity. We have saved quite a lot of money this way and really foreshadowed the push to one university that President Daniels has championed.

One ID card can now also be used at all university libraries to make it easier for faculty and students.

Q: You mention electronic resources. Has the rising cost of acquisitions in this area been a particular challenge?

A: Yes. Over the past 10 years or so, the major publishers started consolidating, and when they did that, it enabled them to be more monopolistic about their products and raise their prices. They have been going up 7, 8, 9 percent per year, some journals even more than that. If we had not banded together to buy as one, we really would be way behind the curve.

Two years ago was when we first spent more money on electronic media than print. Everyone knew that is what would happen at some point, but the tipping point came two years ago.

Q: So much research can now be done remotely: in the office, dorm room, even on a bench with an iPad. Given that, how do you view the future role of the physical university library space?

A: It’s a very interesting question, and I’ll have to give several different answers.

At the same time that we’re expanding the MSEL with the Brody Learning Commons, the Welch Medical Library is looking to get rid of its main library altogether. APL has already done that, a couple of years ago. In a sense, the Welch Library already works as more of a virtual library, with staff ready to go out to where the faculty, researchers and clinicians are because now nearly everything these people use is online. Same is true at APL.

But we have totally the opposite situation here at the Homewood campus. The Eisenhower Library is getting to be more and more used in person, which is why we needed the Brody Learning Commons. Undergraduates love to be in the library working, even though probably 90 percent of what they are using would be accessible in the dorm room. What is not in the dorm room is quiet, or the ability to be “seen to be studying.” That matters a lot to Johns Hopkins students. They tell us this. Then there’s also been an increase in the need for group study and group projects.

This in-person use really accelerated dramatically when the Charles Commons residence building was built across the street. Since it opened [in fall 2006], we’ve seen an exponential growth in library use at Homewood. We had over a million gate count last year, which is a lot of visitors.

When you see what Johns Hopkins Medicine and APL are doing, it’s because of what their users need to have, same as us building a new 42,000-square-foot space because that is what users here on Homewood need. Peabody is still very paper-based because people there still use and need music scores.

Q: In reference to the need for quiet study space, I noticed that when Gilman Hall reopened, the dust hadn’t even settled when students crowded back into the Hutzler Reading Room.

A: I know. It’s shocking [laughs]. We didn’t even announce that the Hut had reopened, or what the hours would be, but they filed back in there. They are just voracious, which, in a way, is fantastic.

That is why we know that with the Brody Learning Commons we can plan and prepare all we want, but when the space opens in July 2012, students will make use of that building in ways that we can’t even imagine. We can try to get ready for it, and be as flexible with the space as possible, but they will get in there and start owning that space.

Q: How much has changed in terms of how students, faculty and staff access online the information we have?

A: One of the biggest challenges is to let people, particularly undergraduates, learn when to use search engines like Google and when not to. These students grew up with these search engines, and too often they assume that whatever you find there is all you need and all you can get. They just take the top hits. So we spend a lot of our time trying to train students when they should be using the databases we have.

We have a redesigned website, but we’ve found that it’s our blogs and Twitter and Facebook accounts that the students actually use more. Almost all the librarians have their own Facebook pages, and that is typically the way students will come at them. Two years from now there might be something completely different.

Although students love to come to the library and work here in groups, they are more likely to reach out to a librarian online. Take last year, when we had all those snow days. Even though we weren’t fully functioning for a few days here, the librarians were online helping students with their work and answering questions.

Q: With so much available electronically, how are we handling the long-term storage/archival aspect of all this information?

A: Actually, it’s a huge concern. Going back to what we were talking about before, we own less and less, and lease more and more. We license this information and do so for one-to-three-year periods. Technically, you could argue that you don’t have access if we stop subscribing, but we rarely stop subscribing.

What we have done as a publishing and library system within the last couple of years is help develop several trusted third-party entities. One is called Portico, a nonprofit that the university and JHU Press joined together. Anything that we license from a publisher gets placed in this dark archive so that if something happened, like the publishers went out of business, we would maintain access to what we had previously purchased or had access to.

It seems to be working fine. But it makes everyone at least a little nervous because it’s not something we can physically touch, like the archives we have in Laurel, Md.

One of the new slogans among large university library systems like ours is that collaboration is the new competitive edge. Someone might take the lead in one area and then share it with the rest. We take the lead in one area, like data curation, and then share it with others—and vice versa.

Q: You chaired the Homewood Arts Task Force in 2006. What came of that effort?

A: We had quite a few recommendations. One of the most important was to have more synchronicity among calendars at Homewood and Peabody, such as the move to a more Monday-Wednesday-Friday class schedule.

Another important one was the creation of the Arts Innovation Program grants, and that continues to this day. One of the major findings of the task force report is that the undergraduates really wanted more for-credit courses in the making of art than were available. So we came up with this idea of Arts Innovation grants. They are relatively small, $8,000 for faculty to create new courses and $2,000 for students to take their arts into the Baltimore community. We gave extra weight to proposals for courses that involved multiple divisions or entities. We have had grants for courses here at JHU and MICA, for example.

These grants have been very successful and laid the foundation for the work of a new arts task force that [Krieger School] Dean [Katherine] Newman asked me to co-chair.

Q: Tell me about the new task force and what your goals are.

A: I’m co-chairing it with [Peabody Director] Jeff Sharkey. We have met a few times and have six to eight faculty from Homewood and Peabody working with us.

We are trying to think of how we might build upon some of the courses that came out of the Arts Innovation grants and how we can learn from that, and how we might collaborate much more effectively with MICA. We can also make more specific recommendations like how we could make the Writing Seminars, theater program and dance program here even more vibrant than they already are. We are asking ourselves whether and how we might strengthen the university if we made the arts more integral to the academic programs of the university.

Q: It will be interesting to see how the Johns Hopkins community embraces this—if more arts is what they want at a school known for science and medicine.

A: Yes. But Jeff Sharkey always reminds people at all of our meetings that we are not called the Johns Hopkins Institute of Technology [laughs]; it’s Johns Hopkins University. I’m happy he keeps making that point.

Q: Getting back to the physical library spaces, do you see much more change throughout the university system?

A: I think we’re done with major changes for now, apart from the Brody Learning Commons. We will also be reclaiming some space. One thing I’m really excited about is getting rid of as many print government publications as we can because they take up huge amounts of space. Many of them are serials that keep growing. They are all online now. I’m hoping to reclaim some space at the MSEL now occupied by such collections for group study areas.

I think that when Welch moves to more distributed functions, that will probably be the end of the major physical changes, at least as far as I can see right now. But a lot of repurposing of space will certainly be going on.

Q: Can you talk about the university’s interest in museums and why we’re involved with cultural institutions like Homewood Museum and Evergreen Museum & Library?

A: It’s a good question. Both museums were given to us. For a long time, I think the prevailing thought was that supporting the museums was Johns Hopkins’ gift to the community. For example, at Evergreen there is an Evergreen House Foundation, and [former owner Alice Warder] Garrett left money to that foundation, which supports roughly half the operating costs, but the rest of the operating costs come from the university. Similarly, Homewood is partially supported by the Merrick endowment.

This community focus was fine, but I also thought that in good conscience we also had to focus on using the museums for Hopkins’ teaching and education mission. Staff in both museums could see that this not only made sense for the future, but they were really excited about it.

We were able to get, very quickly, a very substantial gift from a former Johns Hopkins trustee to endow the course that is now being taught at Homewood Museum each fall. That is really fantastic. The Homewood Museum curator, Catherine Arthur, is teaching this course on material culture as part of the Krieger School’s Museums and Society program: How do you tell historical stories using artifacts? Undergraduates in that course will do an exhibition next month. The same thing is happening at Evergreen, with a few courses there coming through Arts Innovation grants.

But all this doesn’t diminish what we do for the community. We still do exhibitions and welcome people in for tours. But our priority is working with students and getting them to understand what museums are all about.

Q: What is the library system’s role in the community? How do we serve those outside Johns Hopkins?

A: The MSEL is open to everyone. We have a long, strong tradition that anyone who comes in with a photo ID is permitted to use the library. They can’t take books out, but once they come in the door, they have access to our books and thousands of journals and newspapers.

Unfortunately, because of lack of space, we’ve had to reduce that accessibility during exam times, but hopefully with the reopening of the Hut and when the Brody Learning Commons comes online, we won’t have to do that.

We are also actively involved with the public school initiative that President Daniels and Andres Alonso, CEO of the Baltimore City Public School System, started. Everyone at Johns Hopkins has the opportunity to take a few days to spend in the schools. I left it to our library staff to decide whether they wanted to devise some group projects or leave it at the individual level. Our staff chose the Barclay Elementary/Middle School over in the Waverly neighborhood to be our project. A group of 30 have already been there once, and they are going back this month to do some work in the library and whatever else the principal wants.

Q: Anything else you want to talk about?

A: It’s an exciting time to be a librarian. You can plan, but you really never know what is going to happen next, so you can never coast on autopilot. I’m especially eager to see what impact the Brody Learning Commons will have on intellectual and community life at Hopkins.