July 18, 2011

Study: Nonbeating heart cells in scar tissue promote arrhythmia

Team of biomedical engineers and physicists research tissue following heart attack

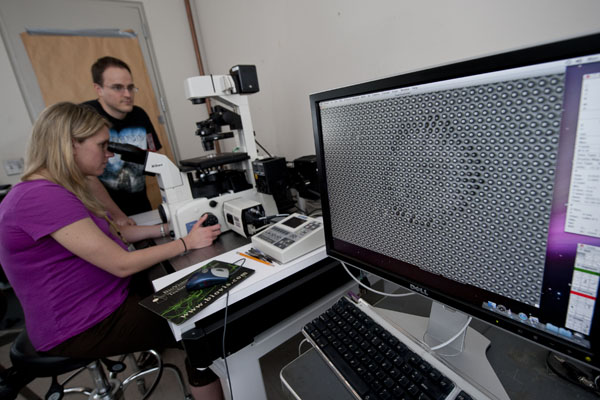

Susan Thompson, of Biomedical Engineering, and Craig Copeland, of Physics and Astronomy, observe a single nonbeating heart cell called a myofibroblast growing on a micropost device. Photo: Will Kirk/Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

Johns Hopkins University biomedical engineers and physicists have completed a study that suggests that mechanical forces exerted by cells that build scar tissue following a heart attack may later disrupt rhythms of beating heart cells and trigger deadly arrhythmias. Their findings, published in the May 17 issue of the journal Circulation, could result in a new target for heart disease therapies.

Principal investigator Leslie Tung, a School of Medicine professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, led a team that looked at how heart cells that beat (cardiomyocytes) were affected by the nonbeating cells (myofibroblasts). Myofibroblasts are called to arms at the site of injury following a heart attack.

“The role of the myofibroblast is to make the injured area as small as possible,” said lead investigator Susan Thompson, a predoctoral fellow in Tung’s Cardiac Bioelectric Systems Laboratory. “Through contraction, the myofibroblasts close the wound and lay down a protein matrix to reduce the scar area. In doing so,” she said, “the myofibroblasts pull on the membranes of adjacent cardiomyocytes. We found that these forces were strong enough to decrease the electrical activity of the working heart cells through mechanical coupling.”

Thompson electrically stimulated cultures containing both the beating and nonbeating cells growing together and found that when the electrical impulses occurred, the nonbeating myofibroblasts pulled on the membranes of beating cardiomyocytes and disturbed their electrical rhythm. Before this study, scientists were aware that myofibroblasts influenced the function of cardiomyocytes by depositing scar tissue, which produces regions of poor or no conductivity in healing cardiac tissue. But the “pulling” scenario described by Tung’s group indicates that myofibroblasts play a more active role than previously realized, Thompson said.

In fact, images created using a voltage-sensitive dye showed that the spread of electrical waves was greatly impaired in the cultures with the most nonbeating cells. Electrical conduction improved significantly, however, when drugs that inhibited contraction or that blocked so-called “mechano-sensitive” channels were added.

“This is a truly exciting discovery because it radically affects our way of thinking about how cardiac arrhythmias might arise,” Tung said.

Tung and Thompson wanted to find out how strong the forces exerted by the myofibroblasts were and whether they changed with the addition of the drugs. So they turned for answers to Daniel Reich, a professor and chair of the Henry A. Rowland Department of Physics and Astronomy in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, and his doctoral student Craig Copeland.

To measure the strength of the contractile forces of the myofibroblasts, the team used a device made up of a platform comprising an array of flexible “microposts.” The array resembled a carpet with widely spaced fibers upon which single cells can grow. As the cells responded to their environment, they pulled on the posts. How much the posts bent provided data about the direction and strength of forces exerted. Single layers of myofibroblasts were grown on the micropost device and tested in the presence of the same drugs that Thompson used in her conductivity experiments.

“Imagine gripping a basketball with one hand, palm facing downward,” Copeland said. “The forces you apply to the ball with your fingertips to keep it suspended are similar to the forces cells exert on their environment. If you were to place your hand on a bed of rubber nails and apply the same gripping force with your fingertips as you did with the basketball, the nails would bend and their tips be deflected. This is exactly what happens with cells cultured on the post arrays.”

Thompson also explained that scientists previously thought that nonbeating cells affected the beating cells simply through openings called gap junctions, where the two cells came into physical contact. The greater electrical charge of the myofibroblasts would flow passively downhill through the gap junctions toward the cardiomyocytes and disrupt their rhythms.

The group’s new hypothesis suggests that another type of membrane channel opened by physical force—the mechano-sensitive channels—may be more important in regulating electrical activity of the cardiomyocytes than mere junctions connecting membranes.

The results of both the conductivity and the micropost experiments fully support this new hypothesis, the team said. Although they acknowledge that both the passive gap channels and the active pulling forces can explain how myofibroblasts affect the electrical activity of cardiomyocytes, the researchers believe that the pulling forces could be more relevant to the development of deadly arrhythmias.

“We are not ruling out the current theory,” Thompson said. “But we are saying there is something else we should be looking at, and we think the pulling forces are a major component. This could provide another lane of therapeutic investigation, especially if drugs could be targeted specifically to the contraction of the myofibroblasts.”

The next step in the project will be to combine the micropost device with electrical experiments on cultures containing cardiomyocyte and myofibroblast cell pairs.

“Although technically quite challenging, it will allow us to unravel how pulling forces applied by the myofibroblast to the cardiomyocyte affect the cardiomyocyte’s electrical activity,” Tung said.

Both Tung and Reich are affiliated faculty members of the Johns Hopkins Institute for NanoBioTechnology. Thompson and Copeland are fellows in the institute’s National Science Foundation–funded Integrative Graduated Education and Research Traineeship.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association and the NSF IGERT.