August 15, 2011

Joseph Brady, pioneering behavioral neuroscientist, dies at 89

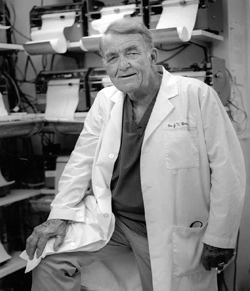

Joseph Vincent Brady, an internationally renowned behavioral scientist and a Johns Hopkins faculty member for more than 40 years, died July 29 at the age of 89.

He will be remembered, his colleagues say, not just as a researcher but as a revered teacher and mentor, successful program builder, avid boater and engaging man with a rich sense of humor.

“Joe was a pioneer in the field of behavioral sciences,” said J. Raymond DePaulo Jr., the Henry Phipps Professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. “The addition of that phrase to our departmental title came at his suggestion. The change signaled the full-fledged acceptance of working behavioral science into our ways of understanding and treating our patients. It came thanks to Joe’s commitment to research that would reveal the power of environmental factors to change behavior for good or ill.”

At Johns Hopkins, Brady not only founded the Division of Behavioral Biology and promoted the launch of the Behavioral Research Unit but also founded the department’s first Behavioral Medicine Clinic. He also was a legendary lecturer in the old Year 1 Psychiatry course for medical students, and was instrumental in founding the original behavioral biology major in the School of Arts and Sciences.

“Additionally, his work helped establish standards used by the FDA, as well as put in place benchmarks for the ethical treatment of human subjects,” DePaulo said. “His research lent substance to new approaches to the prevention and treatment of drug abuse. We’re indebted to him for founding Hopkins’ first behavioral medicine clinic and promoting the launch of our Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit.”

Brady was born in New York City in 1922 and received a bachelor of science degree from Fordham University in 1943 before serving as a combat infantry platoon leader during World War II. After the war, he attended the University of Chicago under an Army training program and earned his doctorate there in 1951. He joined the Johns Hopkins faculty in 1967 and retired from the Army in 1970.

From 1951 to 1970, Brady served as chief of experimental psychology and deputy director of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Bethesda, Md., and it was during that time that he began work with three subjects that would become more well-known than he: Able, Baker and Ham, monkeys who helped pave man’s way into space. Brady trained the three primates to withstand the stresses of space travel, and Able and Baker’s successful minutes-long voyage landed them on the cover of LIFE in June 1959. In 1961, Ham made a longer trip during which he performed Brady-taught tasks, setting the stage for Alan Shepard’s and John Glenn’s first flights into space.

In 1960, Brady founded the Institute for Behavioral Research—now the Institutes for Behavior Resources—a nonprofit institute for animal research and human behavioral research located in Baltimore; 40 years later, he bought a building on Maryland Avenue for the IBR and renovated it to also serve as home for an innovative substance abuse program that now serves more than 500 patients daily.

On May 2, the IBR celebrated its 50th birthday, and colleagues gathered in Baltimore to celebrate Brady at a conference held in Johns Hopkins’ Hurd Hall and at an IBR gala at the American Visionary Art Museum. Brady, DePaulo said, “enjoyed himself immensely.”

To celebrate Brady that day, the IBR compiled “Tales of Joe,” described as “a compilation of stories, letters and anecdotes expressing love, respect and gratitude for Joe Brady from students, colleagues and friends.”

The pages tell a story of a man as dedicated to his students and his sense of fun as to his work; of a “gardener” who cultivated, grew, promoted and disseminated generations of scientists; and of a world-renowned legend who had all the time in the world for a 10-year-old girl working on a school project, who went on to earn a PhD in science.

Brady is survived by his fourth wife, the former Nancy Heaton; a son; four daughters; a stepdaughter; a brother; 13 grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.