October 3, 2011

Orbital observations of Mercury reveal unprecedented surface detail

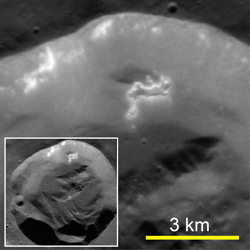

This high-resolution view shows a small, fresh 15 km–diameter impact crater (inset) at a high northern latitude on Mercury. Bright material is exposed on the upper part of the south-facing wall, and hollows are present on a section of the wall that has slid partway down toward the floor. Photo: Science/AAAS

After only six months in orbit around Mercury, NASA’s Messenger spacecraft—built and operated by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory—is sending back information that has revolutionized the way scientists think about the innermost planet. Analyses of new data from the spacecraft show, among other things, new evidence that flood volcanism has been widespread on Mercury, the first close-up views of Mercury’s “hollows,” the first direct measurements of the chemical composition of Mercury’s surface and the first global inventory of plasma ions within Mercury’s space environment. APL also manages this Discovery-class mission for NASA.

The results are reported in a set of seven papers published Sept. 30 in a special section of Science magazine.

“Messenger’s instruments are capturing data that can be obtained only from orbit,” said Messenger principal investigator Sean Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. “We have imaged many areas of the surface at unprecedented resolution, we have viewed the polar regions clearly for the first time, we have built up global coverage with our images and other data sets, we are mapping the elemental composition of Mercury’s surface, we are conducting a continuous inventory of the planet’s neutral and ionized exosphere, and we are sorting out the geometry of Mercury’s magnetic field and magnetosphere. And we’ve only just begun. Mercury has many more surprises in store for us as our mission progresses.”

For decades scientists had puzzled over whether Mercury had volcanic deposits on its surface. Messenger’s three flybys answered that question in the affirmative, but the global distribution of volcanic materials was not well-constrained. New data from orbit show a huge expanse of volcanic plains surrounding the north polar region of Mercury. These continuous smooth plains cover more than 6 percent of the total surface of Mercury.

The volcanic deposits are thick. “Analysis of the size of buried ‘ghost’ craters in these deposits shows that the lavas are locally as thick as 2 kilometers [1.2 miles],” said James Head, of Brown University, the lead author of one of the Science reports. “If you imagine standing at the base of the Washington Monument [in D.C.], the top of the lavas would be something like 12 Washington Monuments above you.”

According to Head, the deposits appear typical of flood lavas, huge volumes of solidified molten rock similar to those found in the millions-years-old Columbia River Basalt Group, which at one point covered 60,000 square miles in the northwest United States. “Those on Mercury appear to have poured out from long, linear vents and covered the surrounding areas, flooding them to great depths and burying their source vents,” Head said.

Scientists also have discovered vents, measuring up to 16 miles in length, that appear to be the source of some of the tremendous volumes of very hot lava that have rushed out over the surface of Mercury and eroded the substrate, carving valleys and creating teardrop-shaped ridges in the underlying terrain. “These amazing landforms and deposits may be related to the types of unusual compositions, similar to terrestrial rocks called komatiites, being seen by other instruments and reported in this same issue of Science,” Head said. “What’s more, such lavas may have been typical of an early period in Earth’s history, one for which only spotty evidence remains today.”

As Messenger continues to orbit Mercury, the imaging team is building up a global catalog of these volcanic deposits and is working with other instrument teams to construct a comprehensive view of the history of volcanism on Mercury.

Images collected by Messenger have revealed an unexpected class of landform on Mercury and suggest that a previously unrecognized geological process is responsible for its formation. Images collected during the Mariner 10 and Messenger flybys of Mercury showed that the floors and central mountain peaks of some impact craters are very bright and have a blue color relative to other areas of Mercury. These deposits were considered to be unusual because no craters with similar characteristics are found on the moon. But without higher-resolution images, the bright crater deposits remained a curiosity.

Now Messenger’s orbital mission has provided close-up, targeted views of many of these craters.

“To the surprise of the science team, it turns out that the bright areas are composed of small, shallow, irregularly shaped depressions that are often found in clusters,” said David Blewett, a staff scientist at APL and lead author of one of the Science reports. “The science team adopted the term ‘hollows’ for these features to distinguish them from other types of pits seen on Mercury.”

Hollows have been found over a wide range of latitudes and longitudes, suggesting that they are fairly common across Mercury. Many of the depressions have bright interiors and halos, and Blewett says that the ones detected so far have a fresh appearance and have not accumulated small impact craters, indicating that they are relatively young.

“Analysis of the images and estimates of the rate at which the hollows may be growing led to the conclusion that they could be actively forming today,” Blewett said. “The old conventional wisdom was that ‘Mercury is just like the moon.’ But from its vantage point in orbit, Messenger is showing us that Mercury is radically different from the moon in just about every way we can measure.”

Scientists are collecting data about the chemical composition of Mercury’s surface that could not have been obtained without the sustained observing perspective that Messenger’s orbit provides, and that information is being used to test models of Mercury’s formation and shed light on the dynamics of the planet’s exosphere.

Measurements of Mercury’s surface by Messenger’s Gamma-Ray Spectrometer reveal a higher abundance of the radioactive element potassium, a moderately volatile element that vaporizes at a relatively low temperature, than previously predicted. Together with Messenger’s X-Ray Spectrometer, or XRS, it also shows that Mercury has an average surface composition different from those of the moon and other terrestrial planets.

“Measurements of the ratio of potassium to thorium, another radioactive element, along with the abundance of sulfur detected by XRS, indicate that Mercury has a volatile inventory similar to Venus, Earth and Mars and much larger than that of the moon,” said APL staff scientist Patrick Peplowski, lead author of one of the Science papers.

These new data rule out most existing models for Mercury’s formation that had been developed to explain the unusually high density of the innermost planet, which has a much higher mass fraction of iron metal than Venus, Earth or Mars, Peplowski points out. Overall, Mercury’s surface composition is similar to that expected if the planet’s bulk composition is broadly similar to that of highly reduced or metal-rich chondritic meteorites (material left over from the formation of the solar system).

Messenger also has collected the first global observations of plasma ions in Mercury’s magnetosphere. Over 65 days covering more than 120 orbits, Messenger’s Fast Imaging Plasma Spectrometer, or FIPS, made the first long-term measurements of Mercury’s ionized exosphere.

The team found that sodium is the most important ion contributed by the planet. “We had previously observed neutral sodium from ground observations, but up close we’ve discovered that charged sodium particles are concentrated near Mercury’s polar regions, where they are likely liberated by solar wind ion sputtering, effectively knocking sodium atoms off Mercury’s surface,” noted Thomas Zurbuchen, of the University of Michigan, author of one of the Science reports. “We were able to observe the formation process of these ions, one that is comparable to the manner by which auroras are generated in the Earth atmosphere near polar regions.”

The FIPS sensor detected helium ions throughout the entire volume of Mercury’s magnetosphere. “Helium must be generated through surface interactions with the solar wind,” Zurbuchen said. “We surmise that the helium was delivered from the sun by the solar wind, implanted on the surface of Mercury and then fanned out in all directions.

“Our results tell us that Mercury’s weak magnetosphere provides the planet very little protection from the solar wind,” he continued. “Extreme space weather must be a continuing activity at the surface of the planet closest to the sun.”

“These revelations emphasize that Mercury is a fascinating world that is unmatched in the solar system,” Blewett said. “We have barely begun to understand what Mercury is really like and are eager to discover what Mercury can tell us about the processes that led to formation of the planets as we see them today.”