March 5, 2012

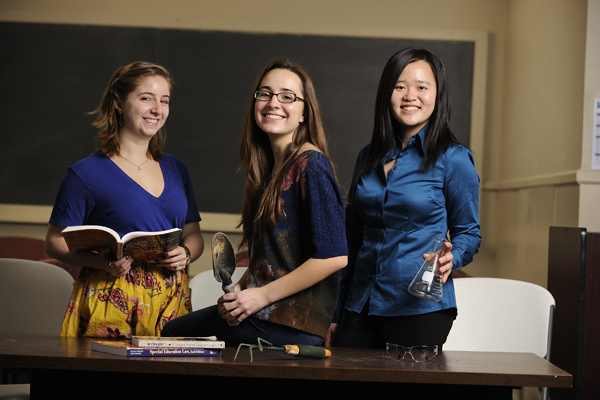

A hat-trick in humanism

Student-run projects aim at social change in Baltimore City

Students who have special education needs face varying degrees of challenges on the path to academic success. And that’s why Liza Brecher, a junior at Johns Hopkins majoring in the history of science, wondered: Why give these students and their families needless red tape and hurdles to contend with on top of life’s daily struggles?

Students who have special education needs face varying degrees of challenges on the path to academic success. And that’s why Liza Brecher, a junior at Johns Hopkins majoring in the history of science, wondered: Why give these students and their families needless red tape and hurdles to contend with on top of life’s daily struggles?

Brecher points to complex IEP (individualized educational program) forms, school system and municipal bureaucracy, and the burden on parents of fitting IEP meetings into a busy work schedule. Then there’s the cost. Advocates—professionals trained to help navigate services—can charge up to $75 an hour.

Brecher wanted to help Baltimore City students and their families find their way through this often thorny special education maze—and to do so for free. And she will, thanks to the $5,000 grant she was given to help fund her project called HEAR, Homewood Educational Advocacy Resource.

HEAR was one of three student-run projects recently awarded funding in the Social Entrepreneurial Business Plan Competition, a new feature in the Homewood intersession course called Leading Social Change.

In the class, the students had the opportunity to develop business plans for projects that would have a positive social impact in Baltimore. The two-credit, three-week class culminated in a competition in which students presented their ideas to peers and a panel of three faculty judges. The top three groups were awarded $5,000 in seed money to turn their visions into reality. The grants were made possible by a $75,000 gift, spread out over five years, from university alumnus Christopher Drennen.

The other two winning proposals were the Baltimore MicroFarming Project and the Charm City Science League.

Bill Smedick, director of leadership programs and assessment in the Office of Student Life, created the Leading Social Change course three years ago to give students real-world and leadership skills to make a positive difference in society. The business plan competition was instituted last year.

This year’s class had 25 students, who broke off into seven teams.

Smedick, who teaches the course, said that the judges had several first-class projects to pick from.

“We had a great group this year—talented students who were all looking to innovate for social change,” said Smedick, an adjunct lecturer in the Center for Leadership Education in the Whiting School of Engineering. “I couldn’t be happier.”

To achieve its goals, HEAR will train JHU and area undergraduate and graduate students to become advocates for families who have children receiving special education services.

Brecher said that the special education system is complex and difficult for parents to navigate, especially with the added challenges of poverty and illiteracy that some in the Homewood area face.

The student volunteers will be trained in the legal aspects of special education, federal regulations, sensitivity issues and the IEP process. “They’ll also become familiar with the specific quirks in the Baltimore City system,” she said.

The Department of Education defines special needs broadly, including everything from autism and blindness, to dyslexia and hearing impairments. Brecher knows firsthand the challenges faced by these families, as her older brother has Down syndrome. Since 2009, she’s volunteered at the Down Syndrome Program at Children’s Hospital Boston.

“My parents worked very hard to ensure [that my brother] received appropriate services,” she said. “And I’ve been around other families who didn’t think their child’s individualized education plan was right, but they weren’t sure how to change it.”

Brecher started to interview applicants for HEAR last week. She plans to select five to seven people, each of whom will partner with one family. The HEAR project will officially start in April.

The Baltimore MicroFarming Project is modeled after similar community-based farms nationwide. The project aims to promote community involvement and goodwill by involving area residents and neighborhood organizations in every aspect of planning and implementing an urban garden.

The project is targeted at refugees and immigrants who were involved in agricultural pursuits in their home countries. Relocated in Baltimore, many refugees have factory jobs and live in “food deserts,” defined as pockets far from a grocery store, said Anna Wherry, a sophomore public health studies major and the project’s leader.

Wherry implemented a similar garden on a smaller scale during her senior year of high school. She said that the experience enabled her to see how participants were able to improve their quality of life.

“With this project here in Baltimore, the participants can use the garden to reconnect with the land, supplement their diet and earn some extra income via the farm’s products,” she said.

The ultimate goal, she said, is to turn this project over to the immigrants whom the project is designed to benefit.

Wherry and the group’s three other students are currently talking to several community organizations interested in the project and are looking for additional funding. They are also looking to secure a two-acre piece of land located within 10 minutes’ walking distance of a refugee settlement. Wherry said that she expects the project to start in spring 2013.

The Charm City Science League aims to increase academic performance in Baltimore City schools with a particular focus on science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, education. Specifically, the program is intended to inspire middle school students through a combination of intensive one-on-one mentoring and participation in Science Olympiad competitions.

Science Olympiad is currently implemented in four Baltimore middle schools. The goal of the Charm City Science League is to bring the successful program to middle schools within the Greater Homewood area, paired with mentoring focused on encouraging creative thinking and making science fun, said team leader Julia Zhang, a junior majoring in molecular and cellular biology.

Currently, only one in 10 Maryland high school graduates is considered “STEM advanced,” meaning that they possess the skills and sufficient knowledge necessary to succeed in some of the most lucrative and fastest-growing professions available. Seventy-two percent of Maryland’s eighth-graders perform at below-proficient levels in science, while 60 percent score at below-proficient levels in math, according to National Assessment of Educational Progress tests.

The Charm City Science League will start with a pilot after-school program in Barclay Elementary/Middle School, with the eventual goal of implementing the program in two additional Homewood-area schools. The project’s two-year trial period will begin this fall.