July 23, 2012

Diagnoses at your fingertips

Two SoM students create award-winning app for mobile triage

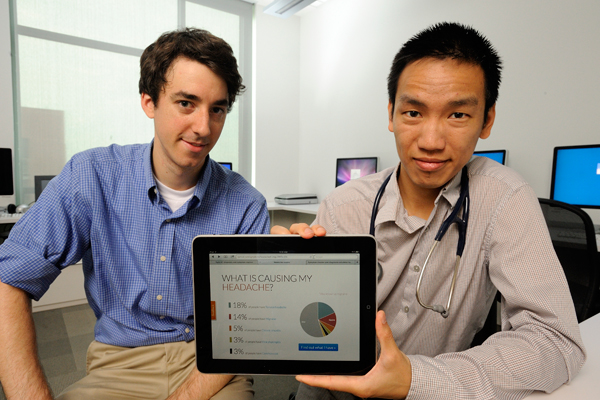

Craig Monsen and David Do show off Symcat, a tool designed to guide consumers to proper treatment for their ailments. Last month the app won the $100,000 grand prize in a competition sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Got symptoms? Two fourth-year Johns Hopkins School of Medicine students have invented a Web and mobile device application to take some guesswork out of what’s ailing you. And they recently won a significant cash prize to take their brainchild to the next level.

Symcat—which stands for symptoms-based, computer-assisted triage—allows the user to enter symptoms (fever, cough, rash, etc.) and receive an instant diagnosis right from a cell phone or computer. Using sophisticated algorithms, the free app ranks the most likely medical conditions and suggests care alternatives based on triage guidelines from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Could that cough be seasonal allergies, or perhaps something more serious?

Last month, the app’s co-inventors, Craig Monsen and David Do, won the $100,000 grand prize in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Aligning Forces for Quality Developer Challenge. The competition, created last fall, asked amateur and professional technology developers from across the United States to create easy-to-use online and mobile device–based tools that would give consumers greater access to health information.

The money will allow Monsen and Do to continue to develop and refine Symcat, which is now available for Android operating systems and online at symcat.com. A version for the iPhone and other Apple products is in the works.

Monsen and Do originally set out to devise a tool to help medical students learn how to prioritize diagnoses and determine the prevalence of various conditions, since many diseases and ailments share common symptoms.

“In medical diagnosis, we are often advised, When you hear hoof beats, think horses not zebras,” Monsen says. “But as we worked on this project, we determined that patients, not medical students or doctors, could benefit the most from such an application. Patients sometimes get needlessly concerned about their symptoms, or they don’t consider that [they] could be something more serious. We wanted to come up with an easy-to-use tool to help determine what could be the cause of their symptoms so that they could act accordingly.”

The algorithm-driven Symcat uses data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The user enters in current symptoms, and then the application asks a series of questions, including how long the symptoms have persisted and about the person’s medical history. The more information a user enters, the more specific are the results returned.

For example, enter in “fever” and “frontal headache” and results for an adult male could range from chronic sinusitis, most likely, to asthma, least likely. Specific percentages are provided for each result. The application also will alert the user if he or she should seek immediate medical assistance.

“Symcat basically guides people through a process and series of questions a doctor might ask,” Monsen says. “The experience is like a dialogue and prods the user to dig deeper.”

Monsen and Do met in 2008 as anatomy lab partners and quickly bonded over their shared passion for engineering projects. In college, Monsen had built an electronic stethoscope for diagnosing heart disease. Do designed a handheld “person detector” for the visually impaired that is able to distinguish a human in the device’s infrared camera view from an inanimate object, even a mannequin.

Before working on Symcat, the pair collaborated on a software application to extract information from electronic medical records for research purposes, a Web-based fitness tracking system and a student Web portal now used widely in the School of Medicine.

They started work on Symcat last July. Encouraged by faculty advisers, Monsen and Do took a leave from school and were accepted into Blueprint Health, a New York–based startup accelerator that provides seed funding and mentorship.

Do says that winning the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation competition has further inspired them.

“The award really validates what we’re doing, harnessing the power of big data and making it palatable to the average person,” Do says. “I think it also demonstrates to our tech-minded peers that there are alternatives to the traditional four-year medical school education.”

Harold Lehmann, director of research and training in the Division of Health Sciences Informatics at the School of Medicine, says that Monsen and Do have done incredible work in designing an application that employs sound research and science, and takes advantage of a wealth of health information.

Lehmann, who served as faculty adviser on the project, says that Symcat, if continually updated with the latest medical findings, has the potential to empower consumers. “A clear benefit here is the ability to aid informed decision making about one’s health,” Lehmann says.

Monsen says he hopes that Symcat can improve health literacy and a person’s ability to communicate with a doctor. He says he also wanted to counter the “Google effect,” meaning what happens when people enter a series of symptoms into a Web search.

“When someone does that, they are not getting results based on medical data but Google’s own algorithm for page rank,” he says. “Sometimes, serious conditions can come up for relatively benign symptoms.”

Monsen emphasizes that Symcat is only an educational tool and not meant to supplant the diagnosis of a trained medical professional and medical tests.

He says that Symcat will continue to improve through the addition of data and its user community’s providing feedback on the app’s diagnosis accuracy. It will also incorporate user reviews of medical providers and care cost information. Ultimately, Monsen and Do want to create a community where patients can help others.

“Our hope is that people get care when they need it and when and where appropriate,” he says. “It’s hard to navigate the health care system. You might ask, Am I overreacting, or do I have a serious problem that needs attention from a medical professional? It’s all about improving access to medical information.”